AIC 2

This is part 2 of my article on AIC. Originally it was part of the original

article but it got so long that I felt it was detracting from the focus of

the original, so I decided to split the article into 2. Please read part 1

if you're unfamiliar with the concept of AIC.

With the knowledge from part 1 you can solve roughly 99.8% of randomly

generated Sudoku puzzles. Everything within this subsequent article builds

on that basic introduction in order to raise that number as close to 100% as

possible. The skill ceiling for Sudoku is extremely high and there are many puzzles

that cannot be solved with classical AIC. To climb the ladder of difficulty

we will have to define more types of strong inferences.

Table of Contents

Grouping Premises

Until now we've only been considering inferences between a single pair of

candidate premises. However if you can prove that a whole set of premises

cannot all be false at once then they form what's known as a

strong inference set, and any division of this set into two subsets

(groups) will give you a strong inference between the subsets. These subsets

can be overlapping, the only restriction is that every element of the

original set has to be in at least one subset.

All instances of a digit in a row, column or box form a strong inference

set. Additionally, all the candidates within a cell form a strong inference

set, but this case is not as easy to make use of.

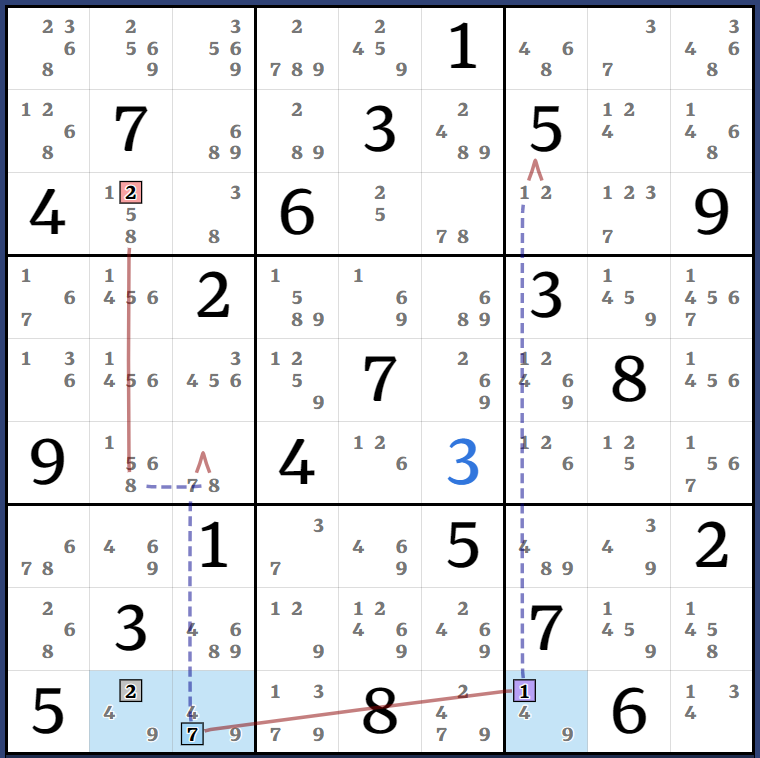

For a practical demonstration, in the example below, the 9s in column 8

form a strong inference set because at least one of them must be true (every

column needs a 9). We can split this into two premises: 9 being in r8c5 and

9 being contained within box 9.

The most practical way to group premises is by mutual weak inferences, as

it allows you to continue the chain.

(8)r1c8 = r1c7 - (8=9)r7c7 - r89c8 = (9)r5c8 =>

r5c8<>8

All the instances of 9 in column 8 form a strong inference set. Notice that

these 9s are contained within 2 boxes, so we can group them into two subsets

depending on which box they're in. This gives us a strong inference between

the two subsets: {9r5c8} = {9r8c8, 9r9c8}.

Three Grouped strong inferences obtained by grouping the candidates in a

row according to the box they're contained in

(1)r4c1 = r4c8 - c8b3 = (1)r1b3 => r1c1<>1

The strong inference set here is comprised of all the 1s within box 3. 1

can be in r1c7, r1c8, r1c9, r2c8 or r3c8. All these cells are contained

within either row 1 (blue), or column 8 (purple), or both (pink) - so I've

grouped them into these two subsets. The grouped link formed by this is

referred to as an Empty Rectangle Intersection (ERI) because

the other cells in that box form a rectangle. Blame whoever

named this move years ago if you find that confusing.

The first group contains the candidate premises 1r1c7, 1r1c8 and 1r1c9. The

second group contains 1r1c8, 1r2c8 and 1r3c8. The fact that 1r1c8 is

contained within both groups means this is an example of a strong inference

where the premises involved do not also have a weak inference - both can be

true if 1r1c8 is true.

Alternatively, you can split these into two groups with no overlap and

still successfully obtain the elimination:

{1r1c7, 1r1c9} = {1r1c8, 1r2c8, 1r3c8}

{1r1c7, 1r1c8, 1r1c9} = {1r2c8, 1r3c8}

But it is simpler to define the Empty Rectangle as the intersection between

a row and a column within a box, hence (1)c8b3 = (1)r1b3.

Adding these Grouped strong inferences to your repertoire will allow you to

solve maybe 50% of the "Beyond Hell" difficulty puzzles on sudoku.coach. But

to solve more than that, we're going to need even more complex strong

inferences.

Almost Locked Sets

An Almost Locked Set (ALS) is a set of N cells within a region that

together contain N+1 unique digits.

(1478)r9c578: 3 cells containing 4 digits

If any of these digits were removed from the ALS you would have a locked

Triple containing the remaining 3 digits. We can use this relationship to

prove new strong inferences. The typical way to do this is to simply say

there's a strong inference between the extra digit and the resulting locked

set. This gives us four strong inferences:

(1=478)r9c578

(4=178)r9c578

(7=148)r9c578

(8=147)r9c578

The locked set's weak inferences are just its potential eliminations, which

is every candidate in a cell that sees every instance of that digit within

the ALS.

(7=184)r9c578 - r8c8 = (4)r8c4 => r8c4<>7

This AIC proves a strong inference between (7)r9c5 and (4)r8c4, so we can

eliminate any mutual peers. It is standard to push the digit that continues

the chain to the end of the LS in Eureka notation to make the continuity of

the chain more apparent, hence (7=184)r9c578.

Only two of the ALS digits are relevant to the chain as a whole - the 4s

and 7s - so I often ignore the rest and treat ALS strong inferences as being

between the two groups of digits, effectively (7)r9c5 = (4)r9c78. Any two

ALS digit sets cannot be false at the same time because then the N cells

would have N-1 unique candidates, meaning it would be impossible to fill

them all. This has the effect that every digit in the ALS is strongly linked

to every other digit.

The same AIC with the strong inference directly between the ALS digits

(4=7).

It's not a big deal which of these you use when chaining, they're both

valid and lead to the same result in the end, so it's up to whichever you

find most convenient.

(1)r1c2 = r1c5 - (1=87)r7c56 - (7=3681)r4567c2- => r28c5<>1,

r7c78<>8, r8c56<>8, r2c2<>1, r12c2<>8,

r6c1<>8

Another important thing to note about ALS is how they act in Rings. Focus

on (178)r7c56.

Recall that when an AIC forms a Ring, all of its weak inferences are proven

to also be strong. By the same token, all strong inferences are also proven

to be weak. This has profound consequences for ALS: if two of the candidate

digits have a weak inference, that means both of them cannot be true at

once. Rephrased, this means exactly one of the candidate digits used in the

Ring (1 and 7) must be false.

As an ALS is composed of N+1 candidate digits in N cells, exactly one of

those candidate digits is false. The Ring just proved that either 1 or 7

must be false, therefore the other candidate digits in the

ALS must be true. In this case the other candidate digit is 8, so we can

eliminate all the 8s that it sees.

Same goes for the other ALS, (13678)r4567c2. The AIC proves a weak inference between (1) and (7), so all the

other digits are locked into the ALS: the ALS must contain 3, 6 and 8.

Almost Hidden Sets

An Almost Hidden Set (AHS) is a set of N digits within a region that are together contained within N+1

unique cells. It can be seen as complimentary to ALS - every ALS has an

equivalent AHS and vice versa.

(56)r9c124: 2 digits contained within 3 cells

If the (56) candidates were removed from one of the AHS's cells, the

remaining cells would become a hidden set. Again we can use this to define

new strong inferences. The Eureka notation for AHS isn't standardised as far

as I know, so I'd like to take the opportunity to advance my own standard

for them. This AHS gives us three strong inferences:

(56)(r9c1 = r9c24)

(56)(r9c2 = r9c14)

(56)(r9c4 = r9c12)

The strong inference is between the premises that (56) is contained within

particular cells in row 9. The weak inferences of an AHS are a bit more

complicated than for ALS: there are cellwise weak inferences for every cell

of the AHS (r9c124), and also regional weak inferences from every cell that

contains only one AHS digit. If this cell was part of the hidden set, it

would have an exposed naked single, so it would eliminate all other

instances of that digit in its row/col/box.

(8=7)r8c5 - r8c2 = r9c2 - (56)(r9c2 = r9c14) =>

r9c4<>8

This AIC proves that at least one of the endpoints (8)r8c5 and (56)(r9c14)

must be true. The AHS weak inference here is cellwise within r9c2.

(9=3)r6c1 - (39)(r5c2 = r5c75) - (1)r5c5 = (1)r6c4 =>

r6c4<>9

This AIC shows off the regional weak inferences from an AHS cell containing

only a single candidate, 3. I extend the convention from ALS to AHS by

putting the cell that continues the chain at the end of the AHS strong

inference (39)(r5c2 = r5c75).

(1)r1c2 = r1c5 - (1=87)r7c56 - (74)(r7c2 = r21c2)- => r28c5<>1,

r7c78<>8, r8c56<>8, r2c2<>18, r1c2<>8

As this is a Ring all the weak inferences are also strong inferences and

vice versa - the strong inferences are all weak inferences.

This has important ramifications for an AHS: we just proved that in the

pink AHS the strong inference between (47)r7c2 and (47)r1c2 is also weak,

so both cannot be true at the same time - recall that an AHS is formed

from N digits being present within N+1 cells.

If we know that two of the cells cannot both contain AHS digits, that

means one of these two cells must not contain the

AHS digits, which further implies the other AHS cells must contain

the AHS digits, therefore we can eliminate every other candidate from

them. In this example, 1 and 8 are removed as candidates for r2c2.

- - -

You won't see AHS often on Sudoku websites. There are two main reasons for

this: the first is that they're quite hard to spot when you scan the grid,

they are "hidden" after all. I miss hidden pairs all the time when I'm

solving puzzles.

The second reason is that most of the time there's an equivalent ALS that

can achieve the same thing. Here are the first two examples from this

section with their AHS replaced by the equivalent ALS:

(8=7)r8c5 - r8c2 = r9c2 - (7=148)r9c578 => r9c4<>8

(9=3)r6c1 - (3=41)r5c28 - r5c5 = (1)r6c4 => r6c4<>9

So the major use-case for them is to simplify a chain by replacing for

example a 7-cell ALS with a 2-digit AHS. However, there is a rare case where

two AHS can intersect in such a way that there is no equivalent ALS. I wrote

about it further in another article so I'll only show one example.

(514)(r4c9 = r4c342) - (2695)(r4c2 = r1589c2) =>

r9c9<>5

This is an AIC formed by two intersecting AHS. The weak inference (14)r4c2 - (29)r4c2 is easy to prove as all the candidates are

contained within the same cell, so both AHS cannot contain that

cell.

There is no equivalent AIC that you can obtain by replacing these AHS by

their ALS counterparts, as their counterparts are actually two intersecting

AALS (N+2 candidates in N cells).

Kraken Fish

If a candidate digit's locations in N base regions are contained within N

intersecting regions then you can eliminate that candidate from all non-base

positions in the intersecting regions. This is called a Fish and the common

cases are the X-Wing, Swordfish and Jellyfish for N = 2, 3 and 4

respectively.

If however these candidates are contained within N+1 intersecting regions,

this is 1 candidate or set of candidates off of being a Fish, so it's called

"Almost Fish" or "Kraken Fish". This gives us a strong inference between the

Fish and the extra candidates, which are known as the "Fins". The most

common example of this is a Finned X-Wing.

(1)r5c1 = (1)r58/c35 => r46c3<>1

Fishing is a very complicated subject so please refer to the Ultimate Fish Guide for all there is to know on the matter. For the sake of this section

it is necessary to establish some basics.

- Fish are defined by their base sets and their cover sets. If all the candidates of N base sets can be covered by N cover sets, all non-base candidates can be eliminated from the covers.

- If however you require N+1 cover sets to cover all the candidates, you can only eliminate candidates that are contained within 2 cover sets.

- Furthermore, if you require N+X cover sets, you can only eliminate candidates that are contained within X+1 cover sets. The value X is known as the "Rank".

When putting Fish into Eureka notation, you list the base sets first, then

a slash (/), then the cover sets. This Kraken Fish is thusly expressed as

(1)r58/c35.

The Finned X-Wing can be expressed as an N+1 type Fish: (1)r58/c35b4. Box 4

is the extra cover set required to cover all candidates in rows 5 & 8,

and the candidates that are contained within 2 cover sets can be eliminated.

These are the candidates contained within the intersection of c3 and b4. If

the Fish can be resolved into an elimination like this it's not typical to

call it a Kraken Fish, it's just a Finned Fish. "Kraken Fish" implies some

AIC chaining through other digits.

If you find an N+1 type Fish with no candidates contained within

overlapping cover sets then all hope is not lost: you can call the extra

Fins that require the +1 cover set the "Kraken candidates" and define a new

strong inference "Kraken candidates = Fish". This is a whole load of

complicated terminology so another example is in order.

(8)c24/r69 = (8-6)r7c2 = r8c1 - (6=8)r3c1 => r6c1<>8

This AIC proves that the endpoints (8)c24/r69 and (8)r3c1 have a strong

inference so at least one must be true. Both cases would eliminate 8 from

r6c1 so we can safely eliminate it.

The Kraken Fish strong inference is a type of Grouped link: there has to be

an 8 in column 2 so the 8s form a strong inference set. If we divide them

into the two subsets {8r7c2} = {8r6c2, 8r9c2} we have a new strong

inference. The second subset stands for the premise that 8 is only contained

within r69c2, and if this is true then the Fish is true. Again the Fish's

weak inferences (not showcased here) are just its potential eliminations

because the fact the Fish eliminates them means they cannot co-exist - both

cannot be true.

Avoidable Pattern Guardians

An Avoidable Pattern is an arrangement of candidates that provably cannot

be part of the solution. There are two major types of Avoidable

Patterns:

Impossible patterns are candidate arrangements that are simply

impossible to solve, any attempt to fill in the cells according to the

candidates will result in you being unable to do so according to the rules

of Sudoku. This is quite a broad definition with a lot of potential for

interpretation but there are many well-defined impossible patterns which can

be easily recognised. Examples include Bivalue & Trivalue Oddagons and

negative-rank patterns

such as Broken Wing (a single-digit Oddagon).

Deadly patterns are candidate arrangements that can only have

multiple solutions. If they are included within a greater candidate field

then this candidate field either has 0 or multiple solutions. If you know

the puzzle you're solving has a unique solution, removing candidates can

never produce more valid solutions, so if you encounter a deadly pattern

you've made a mistake and ended up in an unsolvable state with 0 solutions.

Examples include

Unique Rectangles and the BUG state.

You absolutely do not want to see an Avoidable Pattern in your puzzle so

you do not want to eliminate the extra candidates that are preventing one

from appearing. The candidates preventing the impossible state are called

the Guardians.

If there is only one of these candidates you can place it as a solved cell,

but if there are more you can treat them as a strong inference set and use

them in AIC - you know that at least one of them must be true.

(2=6)r5c6 - (6=2)r2c28- => r2c1<>2, r2c7<>26

The blue cells would form a Bivalue Oddagon if they all contained {45} so

the extra candidates are the Guardians. They form a strong inference set

which I've grouped by their digits. The resulting strong inference combines

with the bivalue cell (26)r2c6 to form a Ring which is effectively a naked

Pair.

(8)r2c46 = r4c46 - (8=4)r5c5 - r5c4 = (4)r1c4 =>

r1c4<>8

The blue cells here would form a Unique Rectangle if they all contained

{23} so the extra candidates are the Guardians. They form a strong inference set

which I've grouped by their boxes. A short AIC proves a strong inference

between (4)r1c4 and (8)r2c46 leading to one elimination.

Fireworks

Fireworks are a wonderful and surprisingly recent idea, being advanced only

three years ago by shye. The basic gist is that "when a candidate in an intersecting row and

column is limited to the same box, it must be placed in the intersecting

cell".

Take this arrangement of candidates for example. If (1)r1c9 and (1)r9c1 are

both set to false then box 1 would have two separate instances of claiming

candidates, resulting in 1 being placed in r1c1.

It follows that these blue cells form a strong inference set: all of them

cannot be false at once. If they were, you would be forced to place two 1s

in box 1 which is impossible.

In my experience if the Fireworks are only present on a single digit they

have limited utility and most if not all AIC constructed with these links

can be expressed via Kraken Fish instead. Still, the simplicity & added

power when there are two or more overlapping sets of Fireworks (check the

original thread linked above, and

this thread) make it

worth learning.

Equivalence

"Equivalence" is a placeholder name for a particular logical relation

outside of strong & weak inferences. If two premises are always true at

the same time and always false at the same time, these premises are said to

be equivalent, and any resulting structures such as Fish or Locked Sets are

also equivalent.

If you have the strong inference A = B, but you also know B is equivalent

to C - when B is true C is true, when B is false C is false, and vice versa

- then you can swap it out for the new strong inference A = C and all chains

resulting from this are still valid. I tentatively propose that this should

be notated as A = B + C.

These equivalences can be proven under certain circumstances between the

three major logical structures in Sudoku: ALS, AHS and Fish. The three

possible pairs are ALS+AHS, ALS+Fish, and AHS+Fish.

AHS+ALS

In this puzzle row 5 has an AHS (12)r5c258, marked in blue. This gives us

strong inferences between the premises that each of these cells contains the

AHS digits (12).

(12)r5c2 = (12)r5c5

(12)r5c2 = (12)r5c8

(12)r5c5 = (12)r5c8

Note that when the premise (12)r5c2 is true, it clears all other candidates

from the cell r5c2 and the new contents of the cell combine with r2c2 to

form a Locked Pair, marked in purple. When (12)r5c2 is false this Locked

Pair is invalid as the two cells contain too many digits. So the premise

(12)r5c2 can be considered equivalent to the premise that the Locked Pair is

valid, as they always come together. We can represent this as (12)(r5c5 =

r5c82) + (12)r25c2, or the reverse, (12)r25c2 + (12)(r5c2 = r5c58).

(38)(r5c6 = r5c31) + (38)r25c1 - (3)r3c1 = (3)r3c56 =>

r12c6<>3

This puzzle has a similar setup. The premise (3)r5c6 has a strong inference

with (38)r5c1 thanks to the AHS, and this latter premise is equivalent to

the Locked Pair (38)r25c1, so the chain continues from its weak

inferences.

I'm afraid that aside from serving as an introduction to the equivalence

concept, these ALS+AHS combinations are limited in their practicality as (as

far as I know) every instance can also be considered a case of the cellwise

double AHS intersection. Replace the above (38+)r25c1 ALS with its dual AHS

(259)c1, and you get this AIC:

(38)(r5c6 = r5c31) - (259)(r5c1 = r673c1) - (3)r3c1 = (3)r3c56

So the major use-case would be to simplify a complicated chain by replacing

a (for example) 7-cell AHS with its 2-cell ALS counterpart. Disappointing

but I promise the ALS+Fish equivalence is a lot more exciting.

ALS+Fish

In this puzzle row 5 has an ALS (123)r5c28, marked in blue. This gives us

strong inferences between the premises that the ALS contains each of its

candidate digit sets.

(1)r5c28 = (2)r5c28

(1)r5c28 = (3)r5c28

(2)r5c28 = (3)r5c28

Note that when the premise (1)r5c28 is true, it clears all other 1s from the region it is contained

within (row 5), so when this premise is true row 5's possible positions

for 1s are reduced to the strong inference set (1)r5c28. This strong

inference set can be used as a base set for the X-Wing (1)r58/c28. So when

the premise (1)r5c28 is true the X-Wing is valid, but when (1)r5c28 is

false the X-Wing is invalid because the column cover sets no longer cover

every candidate within row 5. The premises (1)r5c28 and (1)r58/c28 are

thus equivalent and can be freely replaced in any AIC.

(9)r123c2 = r6c2 - (9=18)r6c19 + r68/c19 - (8=9)r3c1- =>

r6c25<>1, r6c56<>9, r7c1<>8, r4c9<>8

In this puzzle the premise that the ALS (189)r6c19 contains 8 is equivalent

to the premise that the X-Wing (8)r68/c19 is valid so they can be freely

swapped out. This gives us a Ring with plentiful eliminations.

In Xsudo language this AIC is composed of 5 truths: 9c2, 8r8, r3c1, r6c1,

r6c9. The candidates are covered by the 5 cover sets 1r6, 9r6, 8c1, 8c9,

9b1. 5 - 5 = 0 so the move is rank0.

In fact the entire puzzle is solvable using moves consisting of 5 or fewer

truths, putting it at the lower end of difficulty in this metric - despite

this, its SE rating is 9.0, and it requires Whips and Braids of length 7 to

solve. YZF's solver can't find a single rank0 move - no Rings, ALS-Rings,

Blossom Loops, MSLS, nothing. All this hints that the ALS+Fish equivalence

has a powerful nature inherent to it which makes its eliminations very

difficult to obtain with standard AIC & FC procedures.

(6=57)r2c39 + r27/c39b9 - (7=4)r9c9 - (4=6)r9c4 - r4c4 = (6)r4c1 =>

r12c1<>6, r5c3<>6

Another example except in this case the equivalent X-Wing is Finned so its

only potential eliminations (weak inferences) are (7)r8c9 and

(7)r9c9.

There is also the AHS+Fish equivalence but it's quite redundant as ALS are

easier to use. I won't go into detail but it works the same way by

effectively giving the AHS premises more weak inferences.

Almost-AIC

You may have noticed a pattern in the definitions for ALS, AHS and Almost

Fish strong inferences: each one has a candidate, or set of candidates,

which if removed cause a logical structure to become valid. This gives us a

strong inference with the removed candidates on one side and the resulting

structure on the other side. Can we do this with other logical structures,

such as ALC, MSLS, Sue-de-Coq, even other AIC?

Yes we can. However there isn't much information online on this so I'll

have to advance my own standards and notation. Keep in mind everything in

this section is my own conception of Almost-AIC, born of months of

experimentation and a couple of failed attempts at formalising branching

chains into AIC (my older articles have lots of very very ugly awful moves

because I wasn't as good at finding them yet). There are undoubtedly other

solvers out there with their own procedures, this is just the

conceptualisation that works best for me.

Let's step back and examine our understanding of AIC so far. AIC is formed

by constructing chains via inferences between premises. If these inferences

are valid then the AIC is automatically valid and proves that the endpoint

premises have a strong inference, and in Sudoku we can leverage this new

strong inference to eliminate mutual peers.

If however one of the strong inferences within the chain is invalid, the

AIC is no longer valid and cannot be used to eliminate the candidates. An

example is presented below.

Almost-W-Wing: (2=1)r7c2 - r4c2 = r4c5 - (1=2)r9c5

Most of the AIC checks out but the strong inference (1)r4c2 = (1)r4c5 is

invalid as there's an extra 1 in row 4 preventing these candidates from

being bilocal. We can't assert that both of these candidates can't be false,

because they clearly can, if 1 is in r4c8. As a result these eliminations

are invalid and potentially even incorrect.

Recall that all of the instances of a digit candidate within a single

region form a strong inference set. We can split this strong inference set

into two subsets and as long as the two subsets together contain every

element of the main set, there is a strong inference between these subsets.

Each of the subsets is equivalent to the premise "the location of digit N in

this region is within these cells". Previously we just grouped these by

their mutual row/column/box weak inferences and went on our merry way, but

we don't have to stop the analysis there. We can group these subsets by

their AIC-derived weak inferences.

If I group the strong inference set into the following two subsets:

{1r4c2, 1r4c5} = {1r4c8}

When the left premise is true the strong inference (1)r4c2 = (1)r4c5 is valid and so our AIC is valid. In a sense, the left

premise is equivalent to the premise that the AIC is valid. What we've shown

is that there is a strong inference between this "Almost-AIC" and the

candidates preventing it from being valid.

This has major implications. Any AIC that "almost works" can potentially

have its eliminations rescued by chaining off the extra candidates.

Furthermore, AIC themselves become a premise that we can freely use in

chains, even multiple within the same chain. The weak inferences of an AIC

are simply its eliminations: both cannot be true at once for obvious

reasons.

I like to call the candidates preventing the AIC from being valid the

"Kraken candidates". It's a term derived from Fish, referencing the mythical

Kraken with its many tentacles. I'd say it's accurate here as Kraken AIC

tend to branch out across the entire grid, although the overall structure of

the AIC is still linear.

When it comes to notation, I like to enclose the Almost-AIC in [square

brackets] with the Eureka notation of the Almost-AIC included within. Other

than that there's nothing too special, the rest looks like any other linear

AIC. In diagrams I tend to colour the Kraken candidates in grey and I don't

draw the strong inference between the AIC and its Kraken candidates because

it makes things messy.

Here's a slight modification to the example above allowing one of the

eliminations to be rescued.

(4)r7c6 = (4-3)r7c8 = (3-1)r4c8 = [(2=1)r7c2 - r4c2 = r4c5 - (1=2)r9c5] => r7c6<>2

This AIC proves that the endpoints have a strong inference, (4)r7c6

= [(2=1)r7c2 - r4c2 = r4c5 - (1=2)r9c5]. At least one is true so we may

eliminate all mutually eliminated candidates. The only candidate eliminated

by both the W-Wing and (4)r7c6 is (2)r7c6.

Here are some examples from real puzzles.

[(7=8)r3c6 - r13c5 = r7c5 - (8=7)r7c3] = (8)r5c5 - (8=14)r6c46 -

(4=2597)r1256c1 => r3c3<>7

This is a Kraken Grouped W-Wing, similar to above.

(5)r4c5 = [(8=3)r4c5 - r18/c15 = r1c9 - (3=8)r3c8] - (8)r4c8 = (8-5)r6c9 =

(5)r5c79 => r5c6<>5

The candidates of a cell can be used as a strong inference set in this

manner too. In this example there's a strong inference between (5)r4c5 and

(38)r5c4 and the latter is used in an Almost-AIC (actually another W-Wing

variant containing a Kraken X-Wing).

[(1=4)r8c5 - r8c1 = r3c1 - (4=1)43c2] = [(4=5)r4c2 - (5=8)r3c2 - r3c6 =

(8-6)r2c6 = (6)r4c6] - (4)r4c6 = r7c6 - (4=1)r8c5 => r8c2<>1

The strong inference set (1458)r3c2 is divided into two groups, (14) and

(58). Each of these groups has an associated Almost-AIC. (14) gives us a

W-Wing and (58)'s weak inferences can be chained off in order to reach

around to the W-Wing eliminations. I've coloured the sets in blue and purple

respectively to make the diagram easier to read.

(789)r5c6 = [(1=2)r9c6 - r7c5 = (2-49)r5c5 = (4-1)r9c5 = (1)r45c5] =>

r5c6<>1

In this example the potential Unique Rectangle (12)r59c56 has 6 guardians,

forming a strong inference set. This strong inference set can be divided

into two subsets:

{7r5c6, 8r5c6, 9r5c6} = {4r5c5, 9r5c5, 4r9c5}

The latter of which gives us the AIC (1=2)r9c6 - r7c5 = (2-49)r5c5 = (4-1)r9c5 = (1)r45c5 by grouping the

candidates according to their common cells.

(2)r9c2 = [(8)r3c2 = r6c2 - (8=7)r6c3 - (7=491)r9c237 - (1=2)r3c7] =>

r3c2<>2

In this example the Kraken candidate is an AALS digit. Recall that an ALS

is formed by N cells in a region that contain N+1 unique candidate digits,

and there is a strong inference between every pair of digits.

An AALS is formed by N cells in a region that contain N+2 unique candidate

digits, and every triplet of digits forms a strong inference set.

This strong inference set can be grouped and used in Almost-AIC. This can be

generalised to AAALS, AAAALS, etc. for strong inference sets of quadruplets

and quintuplets respectively.

The same property extends to AAHS - every triplet of cells forms a strong

inference set.

[(2=5)r4c2 - r2c2 = r2c3 - (5=2)r9c3] = (5)r2c7 - (5)r8c7 = [(2=6)r8c7 -

(6=52)r89c3] => r8c2<>2

Here's a delightful move which I like to call a "tie". We have a W-Wing

which is almost valid save for (5)r2c7, and an XYZ-Wing which is almost

valid save for (5)r8c7. Both of these Kraken candidates are in the same

column so both cannot be true at once, therefore at least one of the AICs

must be valid. This Almost-W-Wing and Almost-XYZ-Wing are thus tied together

and their mutual eliminations may be removed. It's really the simplest AIC,

A = B - C = D => A = D, except A and D are both Almost-AIC

premises.

Blossom Loop

Over on the Chinese internet the high-level Sudoku solvers have also been

developing their own theories of branching chains. It's hard for me to know

the full story as there's a significant language barrier but they refer to

Almost-AIC as "Burring Chain", where the chain is the AIC, and the Kraken

candidate is referred to as the "Burr", sometimes "Thorn". You can find a

great wealth of information about the topic in this Baidu group and particularly in this bilibili collection.

One of these Burring Chain techniques is the Blossom Loop, which has been brought to the English-speaking Sudoku sphere by

YZF.

Recall that when chaining, an Almost-AIC's weak inferences are simply its

eliminations. Most AIC will only eliminate one or two candidates so it can

be difficult to get everything to line up and lead to mutual eliminations.

The exception to this is Rings - Rings can have a multitude of eliminations,

even dozens. Chaining off Almost-Rings is a good strategy that can reward

you with easier eliminations.

(7)r6c7 = (7-1)r1c7 = r1c4 - r3c5 = (1-7)r4c5 = (7)r6c5- =>

r1c7<>238, r3c4<>1, r4c5<>2, r6c2<>7

Unfortunately this potential Ring is invalid because column 7 contains an

extra 7. We can declare (7)r2c7 the Kraken candidate and attempt to build an

AIC that rescues the potential Ring eliminations.

While doing this you may run into a situation where the Kraken end node is

one of the potential eliminations of the Almost-Ring, meaning they share a

weak inference. This makes the entire AIC a Ring, including the internal

almost-Ring itself.

[(7)r6c7 = (7-1)r1c7 = r1c4 - r3c5 = (1-7)r4c5 = (7)r6c5-] = (7)r2c7 - r2c12

= (7-9)r1c1 = r1c2 - (9=7)r6c2- => r1c7<>238, r3c4<>1, r4c5<>2, r1c1<>38,

r49c2<>9

This rare technique is called the Blossom Loop. Any strong inference set

can be used for this process - YZF's solver has region, cell and AALS

variants implemented.

[(3=14)r7c78 - r5c7 = (4-3)r4c9 = (3)r9c9-] = (7)r7c8 - r7c23 = (7-5)r8c2 =

r8c1 - (5=238)r126c1 - r6c9 = (8)r4c9- => r7c5,r8c8<>1,

r4c9<>29, r7c4<>7, r8c2<>8, r4c1<>2

Here we have an AALS Blossom Loop built off the strong inference set

between the three AALS digits 3, 4 and 7. As this is a Ring all weak

inferences become strong, all strong inferences become weak, all that is

solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned, and the remaining ALS

digits (in this case it's just 1) are locked into the ALS, so we can remove

all 1s that see the ALS, just like in standard Rings.

---

You've reached the end of the article. Thanks for reading. Applying every

technique as described up to this point will solve almost every puzzle up to

~9.3 SE. This point represents the extent of my current Sudoku solving

capacity, and unless there's an MSLS, Exocet, etc. to lower the difficulty

it's unlikely I'll be able to crack the harder puzzles without extensive

trial and error.

The next step up would be to implement Almost-Almost-AICs but these take

absolutely forever to search for manually and I imagine they would even slow

down a modern computer. I wonder how many "Almost"s you need to solve any

puzzle without fail.

I have some ideas for generalising the "Almost" process into grouped strong

inference sets based on common AIC-derived weak inferences and iteratively

applying this to get the "Almost-Almost", "Almost-Almost-Almost"-AICs etc.,

once I've coded it up I'll revisit the relevant section of this

article.

Comments

Post a Comment